Monsters on the Walls

My grandparents on my father’s side were somewhat wealthy. I spent the first twelve years of my life at their home almost every weekend.

My grandmother, Gladys, was an intolerable woman who surrounded herself with intolerable objects. The mounted head of a taxidermied leopard shared space in her sick-room with a zebra skin rug, along with various figurines made from elephant tusks. A Nazi-looted Chagall would not have looked out of place. The single item that appealed to me was a large, framed display of mostly extinct South American and African lepidoptera. I thought the butterflies were beautiful because of course they were. But even as a child I despised her desire to own their beauty through ostensibly gentle net hunting, methods of killing unknown to me, and finally display by way of ruby or emerald tipped pins.

I had never seen Gladys outside of her sick-room, where despite her enclosure in exotic wealth, she spent her days on a Victorian commode, watching baseball and The People’s Court, the remote control entangled in the gnarlement of her rheumatic, distorted hands.

Everyone is uncomfortable and anxious around the visibly ill. This is normal. We see our future and reasonably find it horrifying.

My grandparents had a Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec lithograph hanging on the wall at the top of the steps that led to my grandmother’s room, where over time I learned to recognize the smells, colours, and self-involved whimpers of lingering death.

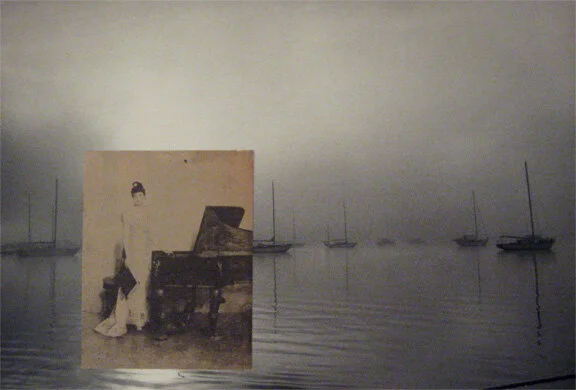

This is the lithograph:

I don’t find it unusual that as a child this image unsettled me. The vantage point leads the eye directly up the subject’s nostrils. I felt the figure to be both looking down at me while trying to summon me into the frame.

The shadow that cleaves her face in two, the smoke-like hair and bared teeth, it all lent the lithograph a sense of foreboding as I’d climb the steps for my obligatory visit to never-not-dying Gladys, who could barely speak but wept with expertise. Her eyes permanently moist and cataracted, pleading in ways that a child could not understand. No child wants an adult to desire their presence so desperately they’re moved to tears. It should be the other way around.

This figure began to represent my grandmother herself. With her hands buried in her pockets, she was the first panel of a nauseating diptych, the second panel was Gladys, whose hands, curled like hawk’s talons, grasping for my small and shaking child’s hands. She was no more than ninety pounds and looked as if she’d shatter if she sneezed, but her ghastly ornithological hand’s ability to maintain its grip was frightening. Each visit ended with me desperately untangling myself from her metacarpal bear-trap, watching as her glass eyes leaked and her mouth made weak animal sounds.

I make Gladys sound bad here for simply being sick. It’s not that though; I have rheumatoid arthritis and a family history of strokes, so will one day be equally ill. Gladys was bad because she’d once hit my father’s head so hard while he was eating that his fork became stuck in the roof of his mouth. She continued, in typical Scottish fashion, to make him ‘clean his plate’, something which must have been extraordinarily difficult with a mouth leaking blood, and with a piece of cutlery now rendered excruciatingly unhelpful.

She died in May of 2000 while I was in Italy, weeping in front of the Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Rape of Proserpina. Weeping because it was just too beautiful, too tender, too impossible. Proserpina’s hyper-realist marble hands had shattered me on the same day my grandmother stopped searching the air for vapours of love or signs of recognition.

To this day that lithograph makes me anxious, and I’ve avoided looking at it while typing this.

*

In 2008 I was not ‘doing well’. My reliance on _____ was at an all time high and my mental health was at an all time low. I found myself in the shittiest part of already-shitty Zurich more often than was necessary, strolling the red light district like a ghost. 2008 was the year I finally landed on the ‘rock on top of rock bottom’.

Things got worse, but by then I’d stopped painting, and this is ostensibly about art.

The year before I had, at that point, my most important exhibition at The _____ ____ in Basel, Switzerland. It could not have gone better. That this didn’t bring me joy plunged me further into depression.

On my way back to Vancouver, I decided to stop in Toronto to see the family I’d become estranged from. I was miserable, angry and confused. The paintings I’d done so well with over the last seven years were frequently described as beautiful, romantic, and intimate. I didn’t want those adjectives used in reviews anymore. I began to feel increasingly antagonistic towards both my audience and the lurid industry I had become a successful member of.

In the suburbs, I went to a nature reserve with a friend of mine who’s now dead to me. We often went there in our twenties to use drugs and take photographs. In October of 2007—now with more expensive drugs and cameras—we walked into the hostile black forest, lit cigarettes, and began to wander through the trees, lighting them up with spotlights, or sitting beneath them, talking about Lee Friedlander and Edouard Vuillard.

We moved off the trail into an area that smart people would use machetes to navigate. I’d always leave the reserve covered in burrs and deep scratches. My paintings were all based on photographs I took, and it was around this time that I’d begun to photograph everything with a flash, a flash and slave flash, or a flash and a spotlight.

My friend and I found ourselves stuck in impenetrable bramble, branches, and reeds. Deep into autumn, the only leaves were under our feet. Our spotlight had died, and I began to blindly photograph the trees, able to glimpse what I was capturing only during the nanosecond when my flash went off. Suddenly we heard the leather-winged sound of bats and panicked, running through the trees until we were back on the trail. The next day my face looked as if it’d been attacked by feral cats.

When I downloaded the photographs to my computer, almost all of them were unremarkable or out of focus. There was a single image that punched me in the stomach, was compositionally perfect, and contained an element of the occult that briefly decreased my disdain for Wiccans.

When I returned to Vancouver, I bought the largest canvas I’d ever used, seven by five feet. After six months of eight hour days in March I was done. I thought the painting to be both perfect and unsettling. I’d created the antithesis to tender intimacy I’d been after.

This is the painting:

In June of 2008 I showed this painting at my last Swiss exhibition, along with similar but less aggressive works intended to induce unease and discomfort. I felt it was more important to trust my instincts than to consider the saleability of my work, which is what all artists of genuine talent have done and should do.

At the opening, a collector who owned much of my work bought what at that point was the most expensive painting I’d made.

This collector was a jolly, rosacea faced banker whose dermatological problems made him either look drunk, extremely happy, or both. I knew that he had two sons and a daughter, as I’d been to his house on multiple occasions to see my work in situ and eat tiny Swiss pastries. His daughter was five years old, and his oldest son around eleven.

The primary appeal of the image I’d painted was the brightly lit, strangely cane or scythe-like branch in the foreground. The shape looked evil to me, as if it marked the entrance to an antechamber of bad dreams. I’d made the painting seven feet high so that it accurately represented the proportions of the area it depicted. Standing in front of it, many people remarked that it looked as if they could walk into it—this was what I’d wanted. I never painted large, but instead of making work that reflected back small replicas of beauty, I wanted to make paintings that could suck the viewer into the canvas, the way my grandparent’s Lautrec sucked me into its frame. Mentally and emotionally, I wished that I could walk into the painting, because while it offered multiple entrance points, there was no exit. I was desperate for a dark space I could disappear into and never return from.

Eleven years later I began to wonder about the traumatization of children by art, after seeing how my niece was terrified by monsters, due to a poster of Shrek that hung in her sister’s bedroom.

After considering how the beloved Shrek had negatively impacted my niece, I began to wonder if a painting like the one above, hung in a home populated by children, could create a narrative that inevitably ended in trauma as those children developed a relationship with it. If I intentionally created this painting to discomfort adults, something that I’d been successful in doing, how would seeing it daily affect the mind of a child? Would they become frightened of the woods at night? Had I created a work that, instead of unsettling gallery visitors, people that I felt disdain for at the time, may instead be generating negative emotions in the mind of a child?

Some images are inherently frightening. I can’t fathom a single child having grown up surrounded by Byzantine icons, or a home stocked with ultra-violent, Renaissance paintings, not being somehow disturbed by the invasion of an unpleasant image into what should feel like a safe space.

Surely legions of Flemish children surrounded by vanitas paintings of decomposing fruit and animals, skulls and signs of decay, must at least have had nightmares. The ways in which imagery (either on its own or in concert with an associated experience) becomes part of its owners personal narrative is a large part of why art is so beautiful. Someone growing up surrounded by Fairfield Porter paintings might develop a love of nature and soft focus. Unless they’d had a parent die in a snowy landscape. Norman Rockwell prints, often considered the most innocent images ever made, might be okay for one child, not so okay for another child molested by a milkman, a police officer, or a purveyor of ice cream.

Personal relationships with artistic works have existed since bison were painted in caves. All personal relationships enable the possibility of trauma. If you cannot speak to the image, powerlessness eventually sinks in. If I told my mother I was more frightened of Gladys’ lithograph than I was of Gladys herself, she would have thought me odd.

Then, abstraction. Maybe images unrelated to reality contain the potential to be neutral, even harmless. Although I myself find nothing in this world more traumatizing than my awareness that the world I live in is an abstraction, one in which I have very little influence. Rothko makes corny people cry.

Shrek, Lautrec—nobody is safe. And these paintings don’t appear every eighteen years, but daily, unrelentingly, in millions of homes all over the world.

Now my paintings are both intimate and off-putting. If I wanted to keep making money and not scare children as I’d been scared, I had to split the difference.

Right now I only paint dark, moody replicas of the NBC Peacock.

Here is one:

Brad Phillips is a writer and artist based in Canada.